In 1918…

The Eiffel Tower was the tallest structure on Earth. From its debut at the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris until the completion of the Chrysler Building in 1930.

“Teenagers” didn’t exist. Yes, young people between 13 and 19 walked the Earth, but no one called them teenagers until the ’40s when high school enrollment became standard. In 1910, only 19% of 15- to 18-year-olds attended secondary school, and a mere 9% graduated.

Woodrow Wilson was president. He’s best known for his foreign policy and leadership during World War I when he urged Congress to “make the world safe for democracy.”

Mary Pickford, called “America’s Sweetheart” and “girl with the curls,” was the biggest silent film star. All of that hair was typical of the “Gibson Girl” archetype that women emulated during the turn of the century. A few years later, the bobs of the Jazz Age would reign supreme.

Social reformer Margaret Sanger coined the term “birth control” by publishing the periodical The Birth Control Review and the book What Every Mother Should Know in 1917. She helped establish a woman’s right to contraception, but not without many legal battles and a 30-day jail stay for being a “public nuisance.”

The average price of bread was 10 cents, butter cost 68 cents, and eggs went for 63 cents. However, a middle-class family only took in about $1,500 per year and saved less than $100 of that annually.

.Inventor Gideon Sundback received the patent for his “Separable Fastener” in 1917. The name “zipper” didn’t take off until the ’20s.

Babe Ruth, “The Bambino,” won the 1918 World Series with the Boston Red Sox,

The first airmail ever was sent in May 1918.

The U.S. had no official national anthem. While “The Star-Spangled Banner” was recognized for official uses, so were a few other songs such as “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” and “America the Beautiful.” “The Star-Spangled Banner” didn’t become the official national anthem until 1931.

The first federal child labor laws were passed in 1916, but it was only ruled to be unconstitutional in 1918. There would be no real regulation until 1938’s Fair Labor Standards Act. The 1910 Census suggests that almost two million kids aged 10 to 15 were working full-time jobs.

Tent Theater

In 1927 an article in the New York Times stated that tented theater constituted “a more extensive business than Broadway and all the rest of the legitimate theater industry put together.” Tent shows were popular in the rural areas of the United States during the first half of the twentieth century, particularly in the Southwest, South, and Midwest. Typically, these shows featured a three-act comedy or drama interspersed with “polite” vaudeville. Great emphasis was placed upon presenting inoffensive family entertainment; the master of ceremonies frequently boasted that “nothing would be seen or heard that might offend the taste of the most fastidious.”

Charles Harrison, one of the leading playwrights of “rag op’ries” and an actor and manager, toured with one of the most elaborate tent theatres ever constructed. Featuring opera-house boxes and a sloping wooden floor with fixed seating, the outfit required three days to erect and a full day to dismantle. While these larger shows, often with companies of over fifty, were appearing in the larger of the small towns, other troupes of varying size, some with as few as a half dozen members in the company, were playing the tiny crossroads communities. The Tent of Stars slips into the latter category easily. We don’t want to be too conspicuous.

The acts:

Sand Dancing: also known as sand jigging, is a type of dance performed as a series of slides and shuffles on a sand-strewn floor. In some instances, the sand is spread across an entire stage. In other cases, it is kept in a box that the dancer stays in throughout the dance. Originally a soft-shoe technique, scratching in the sand can also add a different texture to the percussion of tap. Sand dancing was a specialty act for many vaudeville and music hall performers, including George Burns, who kept it up for decades. The English trio of Wilson, Keppel, and Betty was mainly well known for a routine called “Cleopatra’s Nightmare,” in which they spread sand over the entire stage. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was also well-versed in the art.

Banjo Orchestras: Beginning in the late 1880s, a new fad in banjo-playing bands became “all the rage” In the USA and worldwide. These groups played popular music made up of various-sized banjos such as the Banjo Ukes, Banjo Mandolin, Tenor, Cello, and Bass Banjo. The results were a plucked string version of a brass band. Clear, loud, and exciting, they captured the hearts of young popular music enthusiasts.

Kids in Theater.

The New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, also known as the Gerry society, today a well-respected organization organized to protect children from abuse and exploitation, had a more controversial start. Its co-founder, Elbridge T. Gerry, thought theater was immoral (amusement parks, too) and referred to child performers as “child slaves of the stage.” In the late 1870s, Gerry persuaded the police department to allow the Society agents (nicknamed “Gerrymen”) to keep children away from any “immoral” activities, sometimes by forcibly removing children from their homes. Going after “legitimate theater” was one step over the line for many. Anti-Gerry campaign groups formed, forcing the mayor of New York to limit Gerry’s power and set out proper regulation of child stage performers. Children under 16 were then prohibited from singing, dancing, juggling, or performing acrobatics. This would make Lincoln’s dream of singing on Broadway problematic indeed. He would be allowed a small speaking part if they had a Gerry society permit, and thankfully, he was over seven. Otherwise, he would not be allowed on stage at all.

This ruined the livelihood of many performers like the Keaton family, whose son Buster had been the star of their vaudeville act since he was 3. They bent the law by swearing that Buster was 7.

To this day theatrical producers must still get the Society’s permission for children to go on stage and the group still monitors child actors to make sure they have proper schooling.

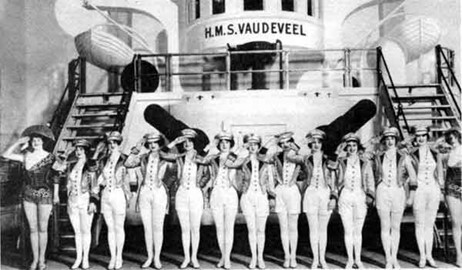

Ziegfeld’s Follies

Born on March 21, 1869, in Chicago, Florenz Ziegfeld showed a passion for showmanship from the start. He enjoyed theater and participated in a number of amateur productions. When the Chicago World’s Fair rolled into town in 1893, Ziegfeld’s father encouraged his son to take it as a business opportunity. Ziegfeld found a strongman named Eugen Sandow. With Sandow, Ziegfeld showcased his ability to drum up publicity. While Sandow flexed his muscles at the World’s Fair in Chicago, a rumor spread that two society ladies had visited the strongman in his dressing room. Before long, all the society ladies followed suit — and Ziegfeld’s profits skyrocketed. But it was his connection with a French actress named Anna Held that changed everything. According to the story, Ziegfeld met Held in Paris. “Your American girls are so beautiful, the most beautiful girls in the world,” she told him. “If you dress them up chic, you’d have a better show than the Folies-Bergere.”

Held became Ziegfeld’s common-law wife and muse. And before long, Ziegfeld transformed Held’s idea into a New York show: the Ziegfeld Follies. Starting in 1907, Florenz Ziegfeld set out to “glorify” American girls with shows that embraced “erotic abandon.”

His Follies of 1907 opened in July 1907 in New York City, where scantily clad and beautiful chorus girls drew excited audiences. By 1911, his popular performances became known as the Ziegfeld Follies. These shows, which lasted until 1927, featured a mix of comedy, dance, music, elaborate production numbers, and, of course, beautiful girls. During the Follies era, many of the top entertainers, including W. C. Fields, Eddie Cantor, Josephine Baker, Fanny Brice, Ann Pennington, Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay, Bob Hope, Will Rogers, Ruth Etting, Ray Bolger, Helen Morgan, Louise Brooks, Marilyn Miller, Ed Wynn, Gilda Gray, Nora Bayes, and Sophie Tucker appeared in the shows.

“For fear someone will think he has adopted a policy of retrenchment because of the war, Mr. Ziegfeld calls attention to one novelty, a chiffon scene in which the chiffon alone cost $3,000,” The New York Times noted at the time about the Midnight Frolic.

“He also wishes to state that the cost of production approximated $100,000.” But Prohibition, which became law in 1920, took some wind out of the sails of the Midnight Frolic. Previously, guests could buy small bottles of champagne for $64. “The best class of people from all over the world have been in the habit of coming up on the roof… and when they are subjected to the humiliation of having policemen stand by their tables and watch what they are drinking, then I do not care to keep open any longer,” Ziegfeld grumbled to The New York Times in 1921. Then the Depression hit — and the joyful opulence embraced by the Ziegfeld Follies fell out of the zeitgeist. Ziegfeld moved to Hollywood with his new wife, Billie Burke — best known as Glinda the Good Witch in The Wizard of Oz — where he died in 1932.

War, Disease, & Uncertainty

No discussion of the period can be made without the two most devastating events of the early 1900s. On April 6, 1917, the United States of America officially entered World War I. Over the next year and a half, millions of Americans served overseas and supported the nation’s war effort at home. Of the 60 million soldiers who fought in the First World War, over 9 million were killed — 14% of the combat troops or 6,000 dead soldiers per day. The total number of deaths for the U.S. was 117,000.

It must be noted, however, that only 53,402 were battle deaths. 63,114 were non-combat deaths. 45,000 of those died from the Spanish flu.

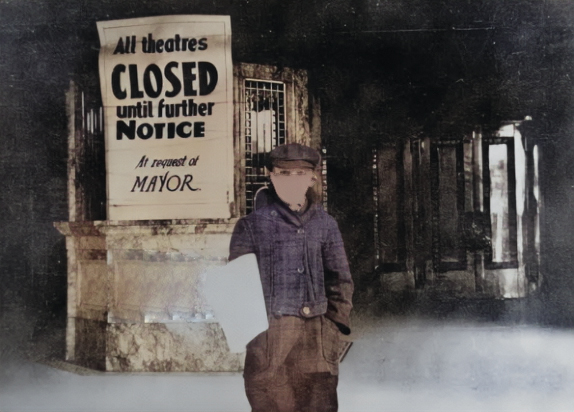

The flu effectively ended the war on November 11, 1918, because the Germans, who had been collapsing already, saw their ranks falling to disease. In truth, no one on either side could continue in the face of the largest depopulating event since the black plague. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide, with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. One-fifth of the world’s population was attacked by this deadly virus. Within months, it had killed more people than any other illness in recorded history. It came in waves, and our story takes place in the summer lull between the first two when most people considered it over. They couldn’t know that the fall wave would claim the most lives during the pandemic.

Between the two events, they brought about a total of 70 million additional deaths in a short span of time. Such a cataclysm jolted society and changed the national zeitgeist. After all the death and fear, it seemed for many that, to escape the darkness, fragile life was to be celebrated, and in a knee-jerk reaction, the over-the-top wildness of the roaring 20s began to emerge.

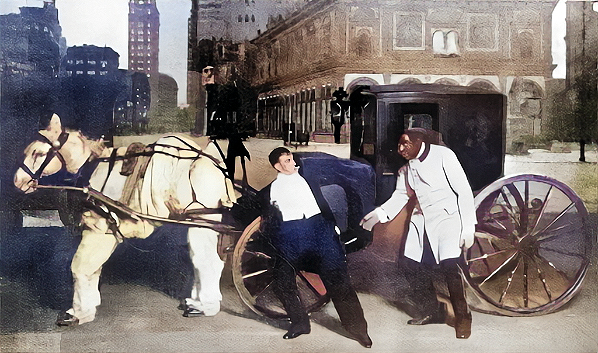

It took the gentile gilded age with it. Cars were replacing horses, electricity was replacing gas and lantern light, swing and jazz were edging out the gay 90s style songs, and carefree abandon was overriding constraint and tradition.

It was at that crossroads where our tent was pitched. Everyone in it had decisions to make. If there was a devil, it was their own they were facing. The Astrolabe is only the shadow that points to the light.

We are today at that crossroads again. Over 1.13 million people have died from Covid in the U.S. alone, wars are changing Europe’s landscape, and society’s norms are giving way to a different future. Each one of us is facing that new reality. Each one of us faces a decision.